Protection From a Pandemic: The Federal Response to COVID-19 in Colorado

Click here to download this report as a PDF

Highlights

- Coloradans will receive a total of $4.85 billion in direct cash stimulus payments.

- For Coloradans who earn the lowest incomes, the cash payments will represent as much as 9.5 percent of their annual pay.

- Colorado will receive more than $2.2 billion in relief for the state government and local governments.

- It’s estimated the $600 bonus unemployment payments to displaced Colorado workers will pump between $150.6 million and $322.7 million into the economy per month.

- The Small Business Administration will be providing forgivable loans to small businesses that employ just under 50% of Colorado’s workforce.

- Colorado could see $385 million in increased costs due to higher enrollment in Medicaid caused by the economic consequences of the outbreak.

- With unemployment spiking due to COVID-19, changes to federal rules mean SNAP benefits will increase for many eligible Coloradans

- Though controversial, provisions regarding financial aid to the airline industry will likely have a larger-than-average effect for Colorado given the $26 billion economic impact of Denver International Airport.

- Public and private efforts at the national, state, and local level must ensure the costs of recovering from this crisis are spread out in a fair and just way.

Introduction

On Jan. 30, 2020 the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced the first person-to-person transmission of the new coronavirus in the United States.[1] As the weeks passed from that first transmission, the virus that causes Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) had already spread to much of the country, including Colorado. At nearly the exact time the first Colorado case of COVID-19 was announced by state health officials, Congress was voting on the first aid package designed to help the country combat the spread of the disease.

The CDC announced a more restrictive recommendation against gatherings of 50 or more people on March 15,[2] followed the next day by guidance from the White House against gatherings of 10 or more people. Around the same time these guidelines were announced, states including California, Ohio, and Colorado began issuing emergency orders for businesses like bars, restaurants, gyms, hair and nail salons, and entertainment venues like movie theaters to close their doors to slow the spread of the virus.

With pressure mounting for a larger federal response to the growing public health and economic crisis, Congressional leaders and the White House came to an agreement that produced a second bill to address the COVID-19 outbreak: The Families First Coronavirus Response Act (FFCRA)[3]. That bill, which was signed into law on March 18, provided necessary initial steps in the response including emergency paid leave, boosts to unemployment insurance and Medicaid, and increased funding for food supports, among others.

On March 27, President Trump signed into law the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act,[4] a third and much larger measure designed to help bolster not only the country’s ability to combat the public threat posed by the virus, but also provide badly needed stimulus to a severely weakened US economy. The CARES Act provided nearly $2 trillion in coronavirus-related aid.

The federal response contains important provisions designed to help individuals and families, businesses, and state and local governments respond to this unprecedented event. This report aims to provide a summary of these provisions and how they will affect Colorado specifically.

Direct assistance to individuals and families

Unemployment insurance provisions

The federal government is bracing for an unprecedented decline in employment — more than 10 million US workers have filed unemployment claims as of early April[5] — and included provisions in the COVID-19 federal relief bills designed to shore up the country’s unemployment insurance (UI) system. The provisions provide assistance to workers who lose their jobs due to the pandemic or whose hours and pay are severely reduced. Financed by a payroll premium on employers for covered workers, this federal-state program provides limited wage replacement to people who lose their jobs through no fault of their own.

Both the FFRCA and CARES provide much-needed support to Colorado’s workforce and economy through UI. The UI provisions are some of the most critical supports for individuals and families in the initial federal response. (Note: for an explanation of Colorado’s current UI system, please see the footnote below.)[6]

The FFRCA provided $1 billion in additional funding to help states provide unemployment insurance benefits.

$500 million will be used to expand eligibility, including waiving typical waiting periods, modifying requirements of claimants to search for new work opportunities, to clarify that leaving a job due to COVID-19-related symptoms falls under the “good cause” exemption to leave a job voluntarily and still be eligible to receive UI payments, and consider COVID-19-related claims to be “non-effective” charges that will not count against an employer’s experience ratings. The FFRCA also provided temporary funding of extended unemployment benefits.

The other $500 million was allocated to improve administration of the benefits. To qualify, states must ensure employers give employees notice of availability of unemployment funds, each state must provide multiple methods to apply, and workers must be able to receive a notification that their claim has been received.

The CARES Act provides major support for states to address shortfalls in their current UI program. Under CARES, $260 billion will be allotted to states to fill in gaps in regular unemployment insurance coverage to include workers who are not typically eligible boost what would otherwise be low wage-replacement rates. This is achieved through three new programs:

- Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (PUC) provides an additional $600 per week to the regularly calculated weekly unemployment benefits, including partial unemployment. This enhanced payment does not count as income that could affect eligibility for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). This provision is estimated to bring between $150.6 million and $322.7 million per month to Colorado through displaced workers.[7]

- Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA)will provide insurance-like benefits to workers who are ineligible for regular UI, including gig workers, self-employed people, freelancers and other independent contractors, seasonal and part-time workers who don’t qualify under Colorado rules, and workers with limited work history. Available through December 31, 2020, the benefit is 50 percent of the statewide average benefit, plus $600 week in PUC (above). Workers must certify that they are partially or fully unemployed and that their reduced employment is due to COVID-19.[8] PUA benefits exclude workers who have ability to telework with pay, and those who are receiving sick leave or other paid leave benefits. The benefits are capped at 39 weeks.[9] The PUA excludes undocumented workers and others not authorized to work.

- Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) provides an additional 13 weeks of unemployment insurance to workers who exhaust all of their regular unemployment. PEUC is fully federally funded. Workers must be actively seeking work, but states must make accommodations for workers unable to find work because of COVID19.

For Colorado, the unemployment provisions in the FFRCA and CARES are incredibly important and desperately needed. It is estimated Colorado will rank high compared to other states for the number of workers displaced due to COVID-19, with the potential for 167,000-358,000 workers to be affected.[10] This projection is backed up in the number of claims the state has already received: Initial UI claims the week of March 14, 2020 were 2,321, roughly the same as the prior calendar year, a number that exploded to over 80,000 claims in the two weeks that followed.[11] While Colorado workers will be eligible for extended UI benefits under the PEUC program, it will not be triggered for at least three months.

Food support

During times of high unemployment, supports like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP, formerly known as food stamps) not only help prevent children and their families from going hungry, they serve as important economic stabilizers.[12] With unemployment skyrocketing, food assistance will once again play a critical role in the lives of families and local economies.

The FFRCA has several provisions related to food support systems, including $1 billion in funding for SNAP, Women and Infant Children (WIC), Meals on Wheels, and free and reduced school lunch programs. In addition to providing a funding boost, the FFRCA suspended SNAP work requirements until a month after the COVID-19 emergency order has been lifted and requires the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to provide emergency SNAP allotments, up to the maximum benefit, for states that request it. Unfortunately, the USDA has interpreted the requirement to provide emergency allotments as only going up to the maximum allowable limit instead of creating an additional allotment. This interpretation means the individuals and families who already received the maximum SNAP benefit, many of whom are among the most affected by this crisis, will not receive any additional benefits.

Even though Colorado’s economy was booming before the COVID-19 outbreak, many families across the state were already leaning on SNAP to put food on the table. In Fiscal Year 2019, about 450,000 Coloradans got food assistance through SNAP and nearly 70 percent of them live in households with children.[13]

As a guide to how SNAP enrollment may grow due to the recession caused by COVID-19, Colorado’s experience during and after Great Recession can provide some guidance. Prior to the recession in 2008, about 250,000 Coloradans were enrolled in SNAP.[14] As the impacts of the recession hit families, enrollment in SNAP drastically increased. Though enrollment declined slightly over the past few years prior to the outbreak, Figure 1 below shows it continues to be significantly higher than before the last recession. As more people lose their jobs and businesses shutter in light of the economic aftermath of COVID-19, Colorado should prepare for a significant increase in enrollment in SNAP programs.

Direct cash payments

The CARES act contains provisions for direct one-time cash payments of $1,200 to eligible adults and $500 for eligible minor children. The cash will be distributed by the IRS using prior tax filings information provided by eligible individuals — individuals don’t need to do anything extra to receive a check. These cash payments will be an important source of income for Coloradans to pay rent, buy food, and meet other financial obligations.

For eligible adults who have not yet filed their 2019 taxes, the rebate will be based on their 2018 taxes. If you have filed your 2018 or 2019 taxes and provided direct deposit, the payment will be deposited in your account. The deposit should arrive by the end of April. Filers who did not provide for direct deposit in their 2018 or 2019 taxes will receive the payment as a check in the mail at the address used for the tax filing. The Bureau of Fiscal Service says the mailed rebates will take longer to arrive than the direct deposit payments.

The amount of the one-time payment is reduced by $5 for every $100 over the phase-out threshold of $75,000 for individuals, $112,500 for heads of households, and $150,000 for joint filers; it would phase out entirely by $99,000 for individuals and $198,000 for couples. In short: tax filers who make less than $75,000 will get a full stimulus check, and for filers with who earn above $75,000 the amount of the check will vary by filing status. Figure 2 below provides a visual explanation of who will be eligible:

The CARES Act defines an “eligible adult” as anyone who is not claimed as a dependent by another tax filer and had a work-eligible social security number in 2018 or 2019. Under this definition, many people will be excluded. College students whose parents claim them as a dependent, stay-at-home spouses who are claimed as a dependent on a working spouse’s tax filings, immigrants who file taxes using Individual Taxpayer Identification Numbers (ITINs), undocumented immigrants who do not file taxes, and workers in the informal economy who do not file taxes will all be ineligible to receive this money. The “eligible adult” definition does include those who receive Social Security Disability (SSDI), worker’s compensation, and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) as income. The one-time cash payments are treated as tax rebates and are not subject to income tax.

For eligible adults who have not yet filed their 2019 taxes, the rebate will be based on their 2018 taxes. For those who have filed their 2018 or 2019 taxes and provided direct deposit, the payment will be deposited in the same account they used when they filed their returns. The deposit should arrive by the end of April. Filers who did not provide for direct deposit in their 2018 or 2019 taxes will receive the payment as a check in the mail at the address used for the tax filing. The Bureau of Fiscal Service says the mailed rebates will take longer to arrive than the direct deposit payments.

Coloradans can expect to receive $4.85 billion in direct cash stimulus payments. While this number seems large, it represents less than 2 percent of total annual income earned in the state. Though the rebates are targeted primarily at low- and middle-income households, Coloradans who earned up to $199k will receive a payment. Approximately 85 to 90 percent of Colorado households will receive some amount of aid as part of the CARES Act.

Figure 3 below shows how meaningful these payments will be to families depending on their income level. For those who earn the lowest incomes, these payments will represent as much as 9.5 percent of their annual pay.

Because the effectiveness of these payments is dependent on the severity and length of the health crisis, how effective these payments will be in preserving Coloradans’ economic well-being won’t be known for some time.

Support for businesses

Small business loans and other provisions

The core component of the CARES Act assistance to small businesses come in the form of loans and grants with $377 billion earmarked for that purpose. $17 billion is allocated to loan subsidies, allowing small businesses to defer loans received through the Small Business Administration (SBA) for 6 months. $10 billion is allocated for the SBA to provide grants to small businesses to cover immediate operating costs. The remaining $350 billion authorizes the SBA and other lenders to issue emergency loans to all businesses with less than 500 employees per physical location, including sole proprietors and independent contractors. In addition to granting expanded access to loans for these businesses, the CARES Act provides additional assistance through loan forgiveness.

The forgiveness provisions are designed to encourage businesses to retain employees and assist business owners to keep the business intact through the crisis. Businesses that end up having their SBA loans forgiven will effectively be having the federal government pay their rent, interest payments and employees’ wages for eight weeks.

Other provisions amend the existing tax code to provide roughly $15 billion a year in tax savings for hotels, restaurants, supermarkets, and retailers, many of which are small businesses. It also provides $670 million for the salaries and expenses of the Small Business Administration, and $275 million for small business development resources, particularly those targeted at assisting women and minority lead organizations.

The federal dollars provided by the CARES Act are necessary to keep Colorado small businesses afloat in these challenging times. These resources will be vitally important in supporting the Colorado economy since small businesses are such a vital component of our business landscape. These businesses are facing a staggering loss of sales or the requirement to transform their business in a matter of weeks in ways they may not be prepared for. Business in the accommodation and food service industry, which is the largest category of Colorado small businesses, will be particularly hard hit, as many have been forced to suspend all business by the state and local governments’ efforts to stem the spread of the virus. Small businesses also have smaller savings and capital, making it more difficult for them to acquire loans than large businesses that may have relationships with financial institutions and large capital stocks with which to back their loans.[15]

Small businesses employed 59.9 million people across the US in 2016, 1.1 million of whom were in Colorado.[16] These jobs comprised 48.2% of the Colorado workforce in 2016. Small businesses owned by women, people of color, and veterans also employ a substantial number of those workers. Figure 4 below shows how many workers are employed by Colorado small businesses owned by people of different races, genders, and levels of military service.

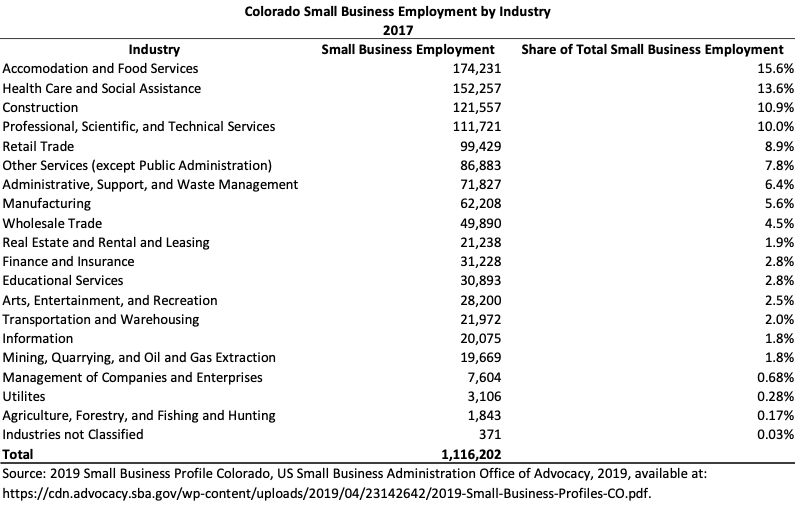

Colorado small businesses are also most likely to be in industries vulnerable to recessions. With most businesses in the accommodation and food service industry forced to suspend operations throughout the state, the loans authorized by CARES will be particularly important. Figure 5 below shows these businesses comprise more than 15 percent of all small business employment. Similarly, Construction and Professional, Scientific, and Technical services experience notoriously sharp drops in sales when consumer and business expenses decrease, and these industries comprise nearly 21 percent of all Colorado small business employment.

Small business loans have been, and will continue to be, an essential component in ensuring the survival of Colorado’s entrepreneurs. These dollars allow companies to expand production, invest in new technology, and grow Colorado’s economy. They will also be essential in allowing small businesses to weather the impact of COVID-19. In 2017, nearly 136,000 loans valued at approximately $2 billion were issued by Colorado lending institutions to small businesses. The SBA also conducted an analysis to show which states receive the most loan dollars per employee. Using estimates from a federal loan program designed to encourage investment in low and moderate-income communities, the Small Business Administration finds that Colorado ranks eighth out of all 50 states in loan dollars per employee.[17] Colorado businesses will likely require a much greater total than the $2 billion issued in 2017 and, by the SBA’s analysis, will most likely require a greater share of any loan relief funds than most other states.

Airline industry aid

The airline industry has argued that it will need significant financial support to remain operable due to severely decreased air travel in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. The International Air Transport Association says the novel coronavirus outbreak could cost airlines as much as $113 billion in lost revenue due to the collapse of air travel.[18] The CARES Act responded with $4 billion in tax cuts, $32 billion in direct grant payments, and $46 billion in loans for the industry.

The CARES Act requires that the grant amounts are used exclusively for the continuation of employee wages, salaries, and benefits. It also restricts companies who receive these grants from conducting layoffs or furloughs and prevents these companies from reducing pay or benefits for employees. Conversely, the law also restricts the ability of companies to increase pay for highly paid employees. Publicly traded companies receiving these grants are also prohibited from issuing dividends or engaging in stock buybacks until September 30, 2021.

While these provisions are controversial, Colorado has a significant economic interest in aid the airline industry. Aviation industry accounts for roughly $28 billion in business revenue and directly employs 20,140 Colorado workers.[19] Almost all of that figure is related to the economic impact of Denver International Airport, which was ranked as the fifth busiest airport in the United States in 2018, serving 64.5 million passengers that year.[20] Aviation is likely to continue to play a large role in Colorado’s economy as direct employment in the state grew 23.1 percent between 2012 and 2017, compared to 4.1 percent growth nationally.

Emergency paid leave policies

The federal response recognizes the critical role that paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave play in helping families cope with health emergencies. Though provisions in the FFCRA and CARES give some recognition of this fact, they still fall short of providing what is needed during normal times, let alone during such a widespread health and economic crisis.

Both the paid sick leave and paid family and medical leave provisions apply to employers with fewer than 500 employees, which includes roughly half of Colorado’s workforce. The FFCRA gave the US Department of Labor the authority to exempt small businesses with fewer than 50 employees and some health care providers and emergency responders. Another provision gives the director of the White House Office of Management and Budget the authority to exclude some federal government employees for good cause.

Both the paid sick and paid medical leave provisions are funded through a refundable tax credit to businesses for 100 percent of costs of qualified leave on a quarterly basis. FFCRA set the cost of this tax credit at $100B and both provisions expire on December 31, 2020.

The FFRCA mandates up to 80 hours, or 2 weeks, of paid sick leave to workers unable to work because of illness, quarantine, isolation, or testing related to COVID-19. It also extends paid sick leave to eligible workers who provide care for a loved one with COVID-19-related symptoms or to their school-aged child if COVID-19 has forced their school to close.

The pay provided for sick leave must be the greater of the worker’s regular rate of pay, the state minimum wage, local minimum wage, or federal minimum wage. Workers can be paid two-thirds of their rate if they are caring for another person or home due to school closure. Sick pay is capped at $511 per day and $5,110 in the aggregate for the worker’s own self-care, and $200 per day and $2,000 in the aggregate, for care of others.[21] Employers may not require employees to utilize other leave prior to taking emergency paid sick leave, nor may they require those employees to cover their own absence during their sick leave.[22]

The FFRCA also temporarily expands the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) to include up to 12 weeks of paid leave because of a public health emergency or to care for a child because daycare or school has closed due to a public health emergency related to COVID-19.[23] Businesses are only required to offer this emergency FMLA expansion if the employee in questions has been employed for at least 30 days. The first 10 days can be unpaid (intended to work in conjunction with the paid sick leave provisions.

The FMLA leave must be paid at an amount not less than two-thirds of the employee’s regular rate of pay and based on the number of hours the employee would otherwise normally be scheduled to work. This leave is capped at $200 a day or $10,000 in aggregate for each eligible employee.

Much like the usual application of FMLA, employers must offer job protection to their employees under this emergency paid family and medical leave with some limitations. Employees who take public health emergency leave are entitled to be restored to their job position or to an equivalent position with equivalent employment benefits, pay, and other terms/conditions of employment after taking leave. This does not apply to employers with fewer than 25 employees or if economic conditions are such that an equivalent position no longer exists.

Aid to state and local governments

Support for public health

One of the most important jobs of the federal government during a pandemic is to coordinate national efforts to contain the spread of the virus. Because the front lines of the fight are taking place at the local level, federal resources will play a key role in the abilities of state and local governments to support efforts to flatten the curve. In order to give them what they need to protect people across the US, the CARES Act allocated $167 billion towards health care efforts to fight COVID-19. The funds are to be spent on specific purposes:

- $45 billion to increase FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund.

- $16 billion to replenish the Strategic National Stockpile.

- $1 billion to bolster domestic supply chains.

- $4 billion to assist federal, state, local public health agencies in purchasing protective equipment, expanding testing lab capacity, and investing in infection control and mitigation strategies.

- $1 billion to support the Indian Health Service response to the coronavirus.

Coronavirus Relief Fund

Among the most important provisions of the CARES Act is a $150 billion relief fund for state, local, and tribal governments. The money is distributed to states based on population and the state allocation must be shared with local governments that have more than 500,000 residents. These relief funds are restricted in several important ways. The bill states that these funds can be used “to cover only those costs of the State, Tribal government, or unit of local government that:

‘‘(1) are necessary expenditures incurred due to the public health emergency with respect to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19);

‘‘(2) were not accounted for in the budget most recently approved as of the date of enactment of this section for the State or government; and

‘‘(3) were incurred during the period that begins on March 1, 2020, and ends on December 30, 3 2020

It is not clear how, if at all, these funds can be used to replace lost state and local revenue due to the economic crisis caused by the virus. However there appears to be great latitude for state and local governments to decide for themselves which expenditures meet the conditions set forth in CARES. The only language that refers to how these use limitations are enforced require that the CEO of the local government (e.g. the governor of a state or the mayor of a city) certify that the proposed uses of the funds are consistent with the three outlined purposes.

Of the $150 billion, the state of Colorado and several of our local governments will get $2.233 billion. Denver, Jefferson, El Paso, Arapahoe, and Adams counties all have populations greater than 500,000 residents. Current estimates suggest those governments will split $559 million of Colorado’s $2.234 billion, leaving $1.674 billion for the state to offset impacts of COVID-19. The money will be released by Treasury to states by the end of April.

Education aid

The CARES Act also includes $30 billion for elementary and secondary schools and colleges and universities for costs related to the coronavirus. Of that $30 billion for the Education Stabilization Fund, $13.5 billion goes to K-12 for formula grants based on the proportion that each state receives under ESEA Title-IA. Colorado will distribute 90 percent of funds to local education agencies based on their proportional allocation of ESEA Title I-A funds. Title I, Part A provides resources to schools for children to receive a fair, equitable, and significant opportunity to obtain a high-quality education. That funding is also intended to help ensure more equitable educational achievement, especially for students of color and students who come from economically disadvantaged backgrounds.[24]

While the allocations for this money have not been released, Colorado received slightly less than 1 percent of total I-A grants in the nation in FY2018, which would translate to $132 million for Colorado schools from that fund.[25] That amount is nearly what Colorado received from I-A federal grants in FY2018 ($152.7 million).

The other 10 percent will be reserved for state education agencies to use for emergency needs as determined by the state, such as coronavirus responses like buying technology to promote online learning.

$3 billion of that $30 billion will go to governors to allocate for emergency support grants to educational agencies and institutes of higher education. 60 percent of that fund will be given to states based their portion of children and young adults aged five to 24 years old, and 40 percent will be given to states based on the number of children younger than 21.

The remaining $14.25 billion for education goes to emergency relief for higher education. The money is distributed to states based on their share of Pell Grant recipients. One big stipulation for those institutional funds is for at least 50 percent of funds to provide emergency financial aid to students that cover expenses under a student’s cost of attendance like food, housing, books, health care and child care.

Additional resources for COVID-19 Response

The bill includes $45 billion for the Disaster Relief Fund for the immediate needs of state, local, and tribal governments to protect citizens and help them respond and recover from the effects of COVID-19.

Transit Agencies

Organizations that provide public transit will get $25 billion distributed through existing formulas or using the FY2020 formulas. There are several federal grant programs including Urbanized Area Formula Grants, Formula Grants for Rural Areas, State of Good Repair Formula Grants, and Growing and High-Density States Formula Grants. The CARES Act gives 280 percent of the FY 2020 appropriations for each of these programs according to the American Public Transportation Association.[26]

Other Fiscal Relief

The act also includes $5 billion for community development block grants (30 percent of which will go to state governments), $3.5 billion for child care, and $400 million to prepare for 2020 elections. States must provide an accounting of how funds were spent within 20 days of any 2020 election.

More funding for Medicaid

Medicaid helps many Colorado families afford the costs associated with doctor visits and other health care costs. The FFRCA included a temporary increase in the matching funds the federal government provides states for Medicaid patients, known as the Federal Medical Assistance Percentage (FMAP). Typically, Colorado’s FMAP is 50 percent. The FFRCA increases it to 56.2 percent. This increase will help the state pay for the increased costs during the period of the declared emergency.

Given the scope of the economic crisis created by COVID-19, it is likely more Coloradans will be enrolling in Medicaid even after the official emergency declaration has ended. It is important to note that the increased reimbursement rate does not apply to all patients and will fall short of covering the increased cost of Medicaid to the state.

How the COVID-19 recession will affect Colorado’s Medicaid enrollment remains to be seen. However, we can look at data from the 2009 Great Recession for clues. During the last recession, Colorado Medicaid enrollment increased by 14 percent.[27] Assuming we see the same number of people applying for Medicaid as a result of the current health and economic crisis, that would mean over 180,000 more people enrolling. Colorado currently spends about $4,900 per Medicaid patient, so for the additional enrollees the cost would be about $880 million.[28] Given the increased FMAP under the FFRCA, the state share of the expected increased enrollment could be around $385 million.

Of course, there are some key differences between the current crisis and the Great Recession that may affect changes in Medicaid enrollment. Since the Great Recession, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has expanded coverage for millions of people including 380,000 Coloradans.[29] The number of uninsured people in our state fell from a peak of 15.8 percent in 2011 to 6.5 percent in 2019.[30] It is still unclear to what extent those affected by the economic impact of the pandemic will lose health insurance coverage. However, based on Colorado’s uninsured rate of 6.5 percent, about 375,000 Coloradans were uninsured prior to the outbreak. The majority of those without insurance earned incomes below 300 percent of the Federal Poverty Level.[31]

Colorado has taken some steps to help address the increased need for affordable health coverage. The Division of Insurance announced a Special Enrollment Period on Connect for Health Colorado, the state’s health insurance exchange authorized by the ACA, which will allow those who are uninsured to apply for insurance. Many of those enrollees will likely qualify for subsidies to lower the cost of premiums. Colorado was also approved for a federal 1135 waiver, which allows greater regulatory flexibility for the Medicaid, Medicare, and CHP+ programs.

Conclusion

Colorado, like the rest of the country and much of the world, is reeling from one of the quickest and most substantial disruptions in our economy and our very way of life in modern history. It remains to be seen just how much longer the outbreak will last and how deeply the economic disruption created by the outbreak will be felt. However, it’s clear this is an unprecedented event and, while the initial response includes badly needed help for families, businesses, and state and local governments, more federal aid will be needed.

And even if the federal government does respond with a fourth round of aid, it is certain that there will be many people across Colorado who will either not qualify for aid or not receive enough of it to prevent deep and long-lasting economic and health consequences.

It will be incredibly important that the federal, state, local, and philanthropic response to this crisis spreads out the costs of recovery in a fair and just way. Otherwise we face the risk of economic inequality, already deeper now than it was before the Great Recession, reaching even more extraordinary levels.

Additional resources

Washington Post: stimulus payment calculator

https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/business/coronavirus-stimulus-check-calculator/

US Senate Committee on Small Business & Entrepreneurship

Guide to the CARES Act

https://www.sbc.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/2/9/29fc1ae7-879a-4de0-97d5-ab0a0cb558c8/1BC9E5AB74965E686FC6EBC019EC358F.the-small-business-owner-s-guide-to-the-cares-act-final-.pdf

The Bell Policy Center’s “Recovery Hub”

https://www.bellpolicy.org/colorado-recovery-hub/

Kaiser Family Foundation: “State Data and Policy Actions to

Address Coronavirus”

https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/state-data-and-policy-actions-to-address-coronavirus/

Colorado Department of Education information on Title I,

Part A

https://www.cde.state.co.us/fedprograms/ti/a

American Public Transportation Association analysis of the CARES

Act

https://www.apta.com/advocacy-legislation-policy/legislative-updates-alerts/updates/cares-act-provides-25-billion-for-public-transit/

[1] https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p0130-coronavirus-spread.html

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/article/coronavirus-timeline.html

[3] https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/house-bill/6201/text

[4] https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/3548/text

[5] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2020/04/02/jobless-march-coronavirus/

[6] Prior to the pandemic, Colorado’s UI system capped the average weekly benefit amount at $460, which replaces between 50-60 percent of wages. In order to be eligible, an employee must have earned at least $2,500 in the prior year. The maximum duration of regular UI benefits was 26 weeks. 85 percent, or about 2.6 million Colorado workers, were covered by regular UI. Workers who are excluded from the regular UI program in Colorado included: Workers not considered employees (independent contractors, those who can demonstrate they are free from direction and control of an employer, e.g. gig workers); people who are self-employed; some part-time nonprofit workers; most agricultural workers; people who perform work outside of Colorado; domestic workers who are paid less than $1,000 in a calendar year; insurance and real estate agents who work on commission; casual labor; people who provide labor for relatives; students working for schools except for interns and nursing students employed by hospitals; youth sports coaches; taxi and limousine drivers; workers without valid work authorization (most notably immigrants and workers with expired DACA).

[7] https://tcf.org/content/commentary/covid-stimulus-3-0-ui-reaction/

[8] https://www.nelp.org/publication/unemployment-insurance-provisions-coronavirus-aid-relief-economic-security-cares-act/

[9] https://cepr.net/the-u-s-response-to-covid-19-whats-in-federal-legislation-and-whats-not-but-still-needed/

[10] https://tcf.org/content/commentary/covid-stimulus-3-0-ui-reaction/

[11] https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/local-news/state-confirms-61-583-coloradans-filed-unemployment-applications-last-week

[12] https://www.coloradofiscal.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/SNAPshot-Why-Food-Assistance-Matters-for-Coloradans-April-2018.pdf

[13]https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/snap_factsheet_colorado.pdf

[14] https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/BRCO08M6

[15] Are Capital Requirements on Small Business Loans Flawed?¸Bams, Dennis, et al., Journal of Empirical Finance, Volume 52, June 2019; Capital Requirements in Supervisory Tests and Their Adverse Impact on Small Business Lending, Covas, Francisco, SSRN 3071918, 2018.

[16] Small Business Profile Colorado, US Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy and Community Reinvestment Act, 2017, available at: https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/25101624/Colorado-2017.pdf.

[17] Statistics of US Businesses, US Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy and Community Reinvestment Act, 2019, available at: https://cdn.advocacy.sba.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/28152825/Appendix_Tables_ 17.pdf.

[18] IATA Updates COVID-19 Financial Impacts – Relief Measures Needed, International Air Transport Association, 2020, available at: https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2020-03-05-01/.

[19] Aviation: Metro Denver and Northern Colorado Industry Cluster Profile, Metro Denver Economic Development Corporation, February 22, 2019, available at: http://www.metrodenver.org/d/m/3T2.

[20] Passenger Traffic Reports, City and County of Denver Department of Aviation, 2020, available at: https://www.flydenver.com/about/financials/passenger_traffic.

[21] https://www.abetterbalance.org/resources/federal-coronavirus-proposal-the-families-first-coronavirus-response-act-h-r-6201/

[22] Ibid.

[23] https://cepr.net/the-u-s-response-to-covid-19-whats-in-federal-legislation-and-whats-not-but-still-needed/

[24] https://www.cde.state.co.us/fedprograms/ti/a

[25] https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R45662.pdf

[26] https://www.apta.com/advocacy-legislation-policy/legislative-updates-alerts/updates/cares-act-provides-25-billion-for-public-transit/

[27] Colorado Department of Healthcare Policy and Financing. (2019, February). Official Medicaid Caseload Actuals and Projection without Retroactivity from REX01/COLD (MARS) 474701 Report.

[28] Kaiser Family Foundation. (2018, November 13). Medicaid’s Role in Colorado. Retrieved from https://www.kff.org/medicaid/fact-sheet/medicaids-role-in-colorado/

[29] Boone, E. (2020, January 27). ACA at 10 Years: Medicaid Expansion in Colorado. Retrieved from https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/aca-ten-years-medicaid-expansion-colorado

[30] Colorado Health Institute. (2020, February 11). 2019 Colorado Health Access Survey: Progress in Peril. Retrieved from https://www.coloradohealthinstitute.org/research/CHAS

[31] Ibid