Denver’s Minimum Wage Impact 3 Years Later

The Colorado Department of Labor and Employment (CDLE)’s new report tracking economic data disputes common claims made by opponents of minimum wage increases that they lead to economic stagnation and growth in unemployment. In the three years following an implementation of its own, higher minimum wage, Denver outpaced the rest of the state in jobs, wage growth, and sales tax revenues, indicating that local minimum wages can be a useful policy tool for localities to advance shared economic prosperity.

For 20 years, Colorado had a law on the books that prevented cities in the state from enacting minimum wages above the state’s level. In 2019, House Bill 19-1210 gave local governments in Colorado back the authority to establish a local minimum wage above the state’s minimum wage. As part of that 2019 bill, the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment (CDLE) is required to write a report regarding local minimum wage laws in Colorado, including economic data on jobs, earnings, and sales tax revenue in the locality with a higher minimum wage compared to neighboring jurisdictions, which don’t.

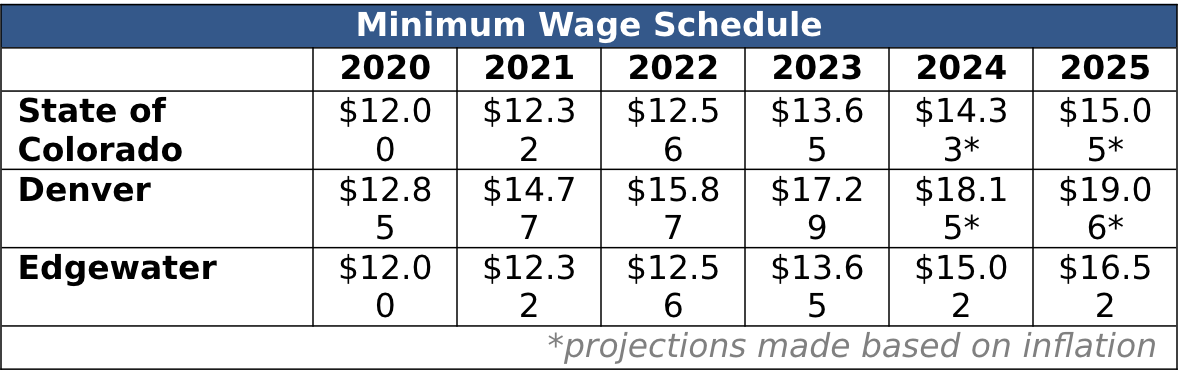

Since 2019, two local governments have enacted a local minimum wage above the state minimum: the City and County of Denver (in 2019) and Edgewater (in 2023).

In May of this year, the Edgewater City Council approved Ordinance 2023-07, which raised the minimum wage to $15.02 for workers in 2024 and is set to ramp up as it nears Denver’s minimum wage in the out years. When Denver’s minimum wage was raised, the initial CDLE report had to rely on limited data that was also impacted by the pandemic.

Now that Edgewater recently passed a minimum wage ordinance, CDLE was mandated to update that report. This updated version will provide a first look at Denver’s minimum wage impact, since it includes more years of data than the initial report, and will be a useful guide for other jurisdictions looking to establish their own local minimum wage.

Denver’s minimum wage schedule went from $12.85 in 2020, to $14.77 in 2021, to $15.87 in 2022, and to $17.29 in 2023 (compared to the state minimum wage of $13.65).

Denver raising its minimum wage creates a natural experiment to compare other parts of Colorado that have kept the state’s minimum wage. CDLE’s analysis takes neighboring cities and comparable localities as the baseline, and then compares what happened to unemployment rates, weekly earnings, and sales tax collections between Denver and the rest of the state.

Opponents of local minimum wage policies claim that such laws cause businesses to cut jobs, cut hours, and pass the higher costs to consumers in higher prices, which can result in fewer purchases. If those claims are true, we’d likely see a drop in jobs, a drop in hourly earnings, and a drop in sales tax revenue collections in Denver, which increased its minimum wage, compared to other jurisdictions, which haven’t.

So, what happened? It turns out that Denver did better all in 3 categories compared to the rest of the state. Unemployment was lower, weekly earnings increased, and sales tax collections all outpaced the rest of Colorado. The opposite of what opponents of minimum wage said would happen, happened.

With a higher minimum wage, Denver’s unemployment rate was better than the rest of the state.

Denver’s unemployment was 5.45% in 2021 compared to 5.9% in the rest of Colorado. As the report states, “Overall, in both 2021 and 2022, as Denver’s minimum wage rose significantly, its unemployment rate dropped more than any comparator jurisdiction’s.”

With a higher minimum wage, Denver’s average weekly wage growth outpaced the rest of Colorado.

In 2020, 2021, and 2022, weekly wages in comparable jurisdictions across Colorado remained stagnant or fell, but in Denver weekly wages grew faster than the rest of the state: by $52.00 in 2020, by $49.67 in 2021, and by $24.67 in 2022. As CDLE notes, “Each of the first three years since its local minimum wage took effect (2020-2022), Denver maintained strong wage growth, and stronger wage growth than Colorado and comparator jurisdictions.”

With a higher minimum wage, Denver’s sales tax collections grew more than the rest of the state and comparable jurisdictions.

Between 2020 to 2022, Denver’s per capita sales tax revenues at restaurants and bars increased by 85%, which was double the sales tax increase in Colorado and comparable cities. The CDLE report explains, “These data show that per capita spending at Denver restaurants and bars has outpaced per capita spending at these establishments statewide throughout 2021 and 2022. Denver not only recovered from a greater reduction in spending in 2020 due to the impact of COVID-19, but experienced more spending—and more growth in spending—at restaurants and bars than comparable cities and counties and the state as a whole.”

If we adjusted for cost of living across counties, what should the minimum wage be?

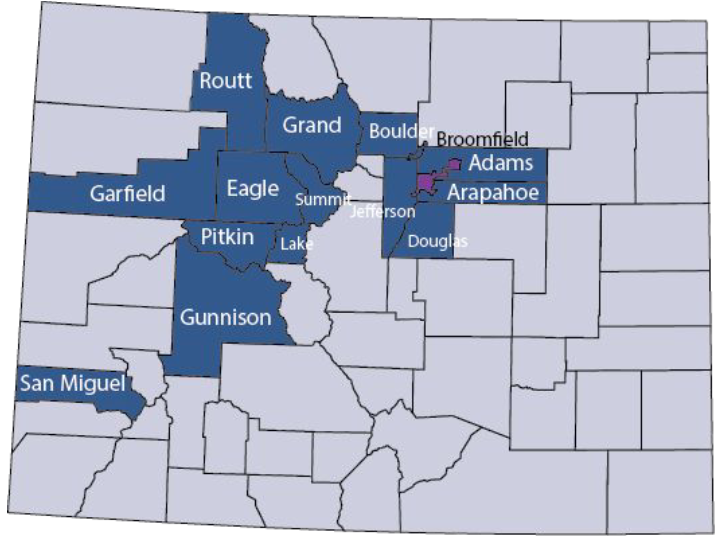

The report also highlights the cost of living across counties in Colorado compared to the area’s minimum wage. The counties around Denver, and Colorado’s ski towns, are all in need of adjusting their minimum wage laws to keep up with their cost of living. For example, in 2021, the adjusted cost of living in Pitkin County (Aspen) would require a minimum wage of $16.04, almost four dollars higher than the statewide minimum wage of $12.32. The map below shows the counties whose minimum wage is below the equivalent minimum wage once adjusted for cost of living.

Counties with high costs of living, including Denver metro counties and outdoor recreation destination counties, can use CDLE’s updated report as evidence to show that increasing local minimum wages does not have disastrous economic consequences; in fact, it has the opposite effect. Boosting income for the lowest-earning people can have rebounding effects for productivity, spending, and tax revenue, making those counties more equitable and prosperous places to live.